One of many wilderness areas in Colorado and throughout the west, providing critical summer range habitat for deer, elk and a number of other wildlife species. As hunter/conservationists let’s do everything we can to preserve and protect public land as well as public land access.

Ashby Bowhunting Foundation Newsletter

July 2025

President’s Message

We are all heartbroken and our thoughts and prayers are with all impacted by the devastating floods that have occurred here in my home state of Texas and elsewhere. THANK YOU to all of those first responders and volunteers helping with the recovery and clean up.

Super Heavy Arrows. Really?

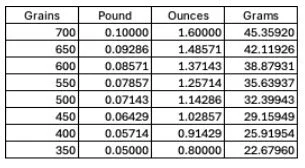

Following last month where I clarified recommend or require based on comments from various groups, another comment that makes its way into the conversations is the arrows we shoot are “super heavyweight” arrows. Nerd out with me a bit this month as I break down these comments using the Avoirdupois Weight System which is the standard weight system in the United States utilized for non-precious items. We all know arrows are weighed in grains and the avoirdupois system shows 1 grain is 1/7000 lb, or .00014286 lb. Sure, 7000 grains sounds like a lot, but it equals only 1 pound. Breaking this down farther into bowhunting let’s take a look at a range of common arrow weights with a total mass of 700, 650, 600, 550, 500, 450, 400 and 350 grains expressed in pounds, ounces and grams to put this in context that can be easily associated with daily life.

A common ink pen, weighing in at 154.2 grains, basically the same as a 150 grain broadhead.

Note the difference between arrows with a total mass of 700 grains and 350 grains is five hundredths of one pound (5/100 lb), or 0.05 lb. Breaking grains down farther and looking at the common weight of a 150 grain broadhead that many have been led to believe is heavy…that is equivalent to the weight of a common ink pen.

Ladies and Gentlemen, an ink pen is NOT heavy! However, it is fact the slightest improvements in overall mass drastically increase the efficiency of many hunting arrow systems. Think of the improvement of that minimal ink pen weight added to a 350 grain arrow, etc. When you hear those crowds whining about ABF and “super heavyweight” or “heavy arrows”, they clearly have an agenda to sell a product to put money in their pocket while trying to be somebody in the archery industry. They are not trying to help you, but rather themselves. Regardless, the correct definition for heavier arrows is simply, heavier, while the lighter arrows are simply, lighter.

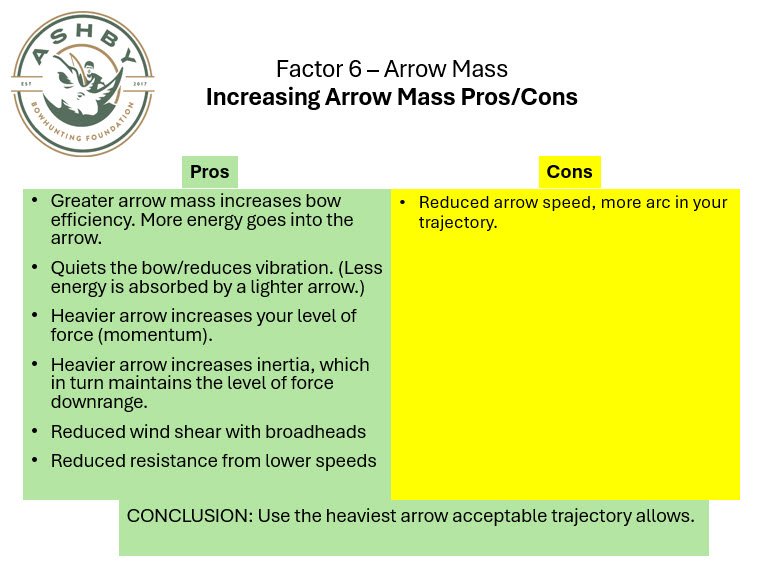

Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of a heavier arrow over a lighter arrow.

Facts are unyielding. As we always state, it is up to the specific bowhunter to determine the hunting recipe that will work every time for them. The animals we hunt deserve the very best we can put forward and no less.

Good hunting and as always, have a nice day.

Rob Neilson

Donations

The Ashby Bowhunting Foundation is a 501 (c) (3) education and research organization. 100% of your donation will go to the Missions of Ashby Bowhunting Foundation. No salaries are paid by the Foundation. We realize there are many worthwhile organizations out there, and greatly appreciate your consideration and support.

Newsletter Tip

More Arrow Weight = More Arrow Momentum = Better Penetration

Many people fear that if they add too much arrow weight, their trajectory won’t be flat enough to hit what they’re aiming at, and therefore they won’t be successful. Reality is quite the opposite. Arrow speed is the most over-rated factor in archery today. An extra 100 to 200 grains of arrow weight will do far more for most hunters’ chances of success than the slightly flatter trajectory they gain by not having it. (page 77, Can’t Lose Bowhuntng by Jeremy Johnson)

Events

September, 2025: Possible testing to gather additional data.

November, 2025: Private Terminal Performance Workshop for a group of international bowhunters.

November, 2025: Recipient of the coveted Dr Ed Ashby Bowhunting Award will be revealed.

WhatsApp Community

If you utilize WhatsApp, ABF has a site inside the Longoria-Hosmer Hunting and Conservation Community. As our readers know, 100% of donations into ABF go to furthering the missions of ABF. The same holds true with the Longoria-Hosmer Foundation where hunters directly support the wilderness and wildlife conservation efforts of the @longoriahosmerfoundation, a 501c3 nonprofit that empowers wildlife and wilderness conservation around the globe. The links are here:

Longoria-Hosmer Hunting and Conservation Community: Open this link to join my WhatsApp Community: https://chat.whatsapp.com/I22hsy6aEZ8BHPbklkvwQg

Ashby Bowhunting Foundation: Open this link to join my WhatsApp Group: https://chat.whatsapp.com/JAs760BctAK8E644dXG1m9

We hope the subscribers of our newsletter will join this one-of-a-kind community. Of course, common sense rules apply…stupid posts will get you kicked out without notice.

Ashby System Results - Bowhunter Interview with Jeremy Johnson

DIY backcountry hunt. Just another non-hero shot moment, representing 99% of bowhunting.

Practicing with friends to watch your form and provide some friendly banter is a great way to test your focus as well as how well you’ve committed your shooting to subconscious. (See Chapter 2 Can’t Lose Bowhunting for more info)

1. How long have you been a bowhunter?

25 years with a bow almost exclusively. Rifle before that. I have nothing against rifle hunting and am not a purist by any stretch, I just love stalking in close!

2. Do you hunt with traditional equipment, compound, crossbow, or a combination of these?

Compound as of now, though Doc keeps hounding me to try his old longbow so I plan on it one of these days. It’s hard for me to change from what works. I do however consider the Howard Hill style of shooting to be the ultimate in bowhunting mastery.

3. What is/are your favorite animal(s) to hunt?

Elk, but it’s the backpack/ mountain style of hunting that draws me more so than the specific animal I’m pursuing. I also like elk because it tastes good, fills the freezer and I can hunt them every year where I live. Mule deer and bear are just as much fun for the same reasons- I love to be in the mountains stalking inside bow range.

4. What is/are your favorite bowhunting method(s): stands, still hunting, spot and stalk, pure stalking, or other?

All methods that involve being on foot. Due to a back injury I’m not much for sitting too long in a tree stand. It’s painful. I do like to know animals are in the vicinity before spending too much time though, so still hunting without prior sighting or hearing of game is hard for my type A personality to want to invest in. I typically kick into rapid reconnaissance mode until something is located, then slow down and savor every step of a stalk. If I can hunt the same animal all day and it takes me hours to get a clear shot, that’s great. I only want to know he’s there.

Here is a bull I killed long before I knew about the Ashby type arrow system. He was blocked in a dry creek bed feeding on alder brush when loosed the first arrow that pentrated about 10 inches. Thankfully he was 10 yards away and trapped on three sides by rock walls. I shot him four more times with the last arrow literally bouncing off of him! The first volley proved lethal and demonstrated just how tough a big old bull of this caliber can be.

5. What event(s) brought you to use Ashby-style arrow setups?

Not getting adequate penetration on elk which resulted in shooting and losing several of them - Thus the name of my book “Can’t Lose Bowhunting”! I vividly remember every arrow I released with precision accuracy only to see half of it hanging out of an elk's side after it hit its target. The elk would then run off like a scalded dog and a long track job ensued. Some of them multiple days and few resulting in a meat haul.

6. Could you describe your typical arrow setup(s) for hunting big game?

Single bevel broadhead with the best steel/edge available, strong insert system, the lightest and stiffest spined carbon arrow in a small diameter. I’m not calling out specifics because I’m trying something new almost every year. I don’t recommend this. My recommendation for guys that just want to hunt and be successful is to find an arrow/broadhead system that works, stick with it for several years and focus your efforts on being the best hunter you can be.

7. Overall, what has been your experience using Ashby-style arrow setups?

Excellent penetration and little to no flight response from the animal when hit. This makes recovery way easier. In addition, a quiet shot and little to no deflection. All important traits for a hunting arrow when dinner is on the line.

8. Do you have any bowhunting tips you would like to pass along?

Get a solid arrow system that incorporates all of the penetration enhancing factors you can. Practice enough to know your proficient range with your hunting bow on your first shot. You’ll get even better if you can do it after running sprints and having a buddy yell at you or tell a joke while you shoot to raise the distraction level and hone your focus. This is closer to the intensity you’ll be facing when hunting in the mountains and gives you a better idea of your skills than just repeatedly shooting targets while fully relaxed.

After that turn your focus to increasing hunting skill. No arrow system, gear or whatever is going to guarantee you success. Don’t try to reinvent the wheel. Use the 12 penetration factors. Buy the best arrow/broadhead insert combination, practice with it and tune your bow to it and then put all the rest of your time and effort into being the best hunter you can be. That is where you will get more encounters and reps with actual animals. Quit wasting so much time on targets and the internet.

Contrast the first bull with this hunt 15 years later. An Ashby style arrow setup zipped through this bull so quietly he didn’t even know he was shot. After looking down the hill at where the arrow landed he took one wobbly step and fell tumbling down the ravine - no tracking necessary. Elk provide more meat than any other animal that I can readily hunt every year. Combine that with the adventure involved in hunting these mountain dwellers and that is probably why I spend more time hunting them than any other animals.

Jeremy Johnson is a lifelong bowhunter, backcountry enthusiast, and author of Can’t Lose Bowhunting. With over 25 years of experience chasing elk, mule deer, and bear in the mountains of the West, Jeremy is passionate about ethical hunting, gear that works, and helping others become better hunters — not just better shots. He lives for the thrill of the stalk and the quiet satisfaction of a well-placed arrow.

From the Field - The Value of Wild Places

There’s a rhythm, a perfect metronome in wild places that can’t be found anywhere else. Wild places are not just scenic backdrops for recreation; they are living, breathing systems that support us in every way imaginable—clean water, clean air, healthy soil, and a deep sense of belonging that no city skyline can replicate. Nature is always striving for harmony, something rarely found in man made environments. Maybe this is why millions of people flock to our national parks and monuments each year. It’s why sportsmen spend time afield. There’s a reason we don’t hunt in Walmart parking lots. These ecosystem treasures look and feel different from a typical neighborhood or even a monoculture farmstead.

This mountain spring, lush with grass and forbs from May through October. Mountain lions keep deer, elk, moose and black bear from overgrazing riparian areas. The health of the ecosystem is maximized by supporting keystone species on the landscape.

At the heart of many of these ecosystems, particularly in the American West, is a species that few people see but whose influence is undeniable: the mountain lion. As a keystone predator, mountain lions shape the behavior of deer, elk, moose, and even black bear. When I started filming and studying mountain lions, twenty one years ago, I realized mountain lions occupied some of the best wildlife habitat I was seeing in Colorado and Montana. At first I thought they were drawn to this habitat. And, in part, that may be so. But there’s more to the story.

By simply existing on the landscape, they push these herbivores and omnivores to stay alert and on the move, preventing them from overgrazing the most sensitive areas—riparian corridors, young forests, and high-elevation meadows. These places, often the green arteries of any ecosystem, where water is filtered, birds and fish thrive, and biodiversity explodes. Without the presence of a top keystone species like the mountain lion, these habitats degrade quickly and with them, everything that depends on them—including us. Beavers are also a top keystone species that have an outsized positive impact on riparian areas.

You can see it on the ground: the difference between a riverbank that has been hammered by sedentary grazers and one where predators keep these animals moving is stark. The healthy banks have willows and aspen regenerating, beaver dams holding water on the land, birds nesting, and insects buzzing in the understory. The water runs clearer and cooler. The soil holds stronger. All of this is amplified by the presence of the mountain lion, who, without a word or footprint we’re likely to see, orchestrates this balance simply through the natural rhythm of hunt and movement. It's predator-prey dynamics 101, and it works—if we let it.

Our benefit from this goes far beyond water quality or scenic value. There’s a part of our DNA that still resonates with the call of the wild, a strand of ancestral memory that understands we need these places not only to survive, but to feel whole. We are hardwired for connection to the wild world. When we lose wild places or strip them of their keystone species, we lose a piece of ourselves. It is a disconnection we often can’t articulate, but one we feel in our bones—in the anxiety of crowded cities, in the longing for open skies, and in the quiet ache we carry when the wild grows distant.

This is why protecting wild places is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. And it’s why respecting and understanding the role of species like the mountain lion is critical to ecosystem health and to our own future. Let the lion roam, let the elk stay wary, let the rivers run wild and clean. In doing so, we protect more than land. We protect the very rhythm that makes us feel alive.

Celebrating the WILD in wildlife,

David Neils

Doc’s Ramblings

Dr. Ed Ashby with a southern bushbuck

The first and most obvious factor is the physical capability of the bow and the arrow. Not all bows and all arrow setups are created equal. A bow capable of shooting an arrow accurately at 40 yards may not be as effective at 50 yards, and certainly not at 60 yards. The arrow's structural integrity, quality of flight, on-target force (momentum), and penetration potential are integral parts of the equation.

There is no universal "maximum distance" because it is tied not only to your shooting skill but also directly to the equipment being used. It is vital to understand the terminal performance of your broadhead and arrow, as penetration power diminishes with distance, especially in a real hunting scenario where angles and obstacles (like brush) may come into play. For any bowhunter, knowing the limits of your arrow's setup—through practice and careful observation—is essential in determining your ethical shot distance.

Second, a bowhunter's proficiency is as critical as their equipment. It's one thing to make a single bullseye during target practice; it's another entirely to hit that same mark when adrenaline is coursing through your veins, the wind is shifting, or the animal is moving.

Experience allows a hunter to gauge their shot distance accurately, and practice under conditions that simulate the real hunt is the only way to honestly evaluate this. The difference between a 20-yard shot and a 40-yard shot might seem negligible on paper. However, the complexity of human judgment and the variability of hunting situations mean that precision declines as distances increase. A successful bowhunter understands that proficiency doesn't just come from shooting at targets in a controlled environment, but from training under varying and unpredictable conditions.

Another consideration is the angle at which the shot is taken. A 20-yard broadside shot on a stationary deer is quite different from a 20-yard shot at a deer quartering away, or up or down hill. Shot angles, along with the animal's reaction, can dramatically change the effectiveness of an arrow and the likelihood of a clean kill. What might be an ethical distance at one moment may no longer be ethical when the shot angle or the animal's body position changes. Bowhunters must continually assess not only the distance but also the geometry of the shot. If you can't ensure a solid hit into the vitals due to the angle, the shot becomes unethical regardless of how "close" you are to the animal.

Finally, environmental factors—such as wind, lighting, and cover—play a massive role in determining your kill zone - your ethical shot distance. Even the most skilled bowhunter will experience a drop in accuracy in windy conditions or when visibility is poor due to low light or brush. These factors all degrade the likelihood of a perfect shot, and the skilled bowhunter must take them into account when setting their personal maximum shot distance in each individual situation.

No bowhunter is ever "entitled" to a shot. You must earn every shot. You must always respect the animal. "Close enough to kill" is dynamic and can vary with each hunting shot. Just because an animal presents an opportunity doesn't mean it's an ethical shot. Only when you have the confidence in your skill and the assurance that the shot will result in a quick, humane kill, should you pull the string.

Good hunting, my friends,

Dr. Ed Ashby

Close Enough to Kill

Now, in all of my bowhunting (and firearms hunting, for that matter), I have always operated on the principle of "close enough to kill". Close enough to kill means knowing the range at which you can keep all your shots well within the kill zone on the animal(s) you are targeting, under the prevailing conditions, and then shooting only within that 'kill zone' for the current shooting position and hunt conditions. It also implies developing your hunting skills to consistently place you within that kill zone, "close enough to kill".

The range that falls within your kill zone can also change, depending on many factors. One is the urgency of making a killing shot with absolute certainty. You might be able to keep your shots within the kill zone of a large, dangerous game animal at a great distance, because the target's kill zone is larger, but never forget that the animal gets a vote. The consequences of making a poor shot on a large, dangerous animal mean a nerve-racking follow-up that has the potential to be damaging … or fatal. The more dangerous the game, the closer you should get before shooting. When the animal is big and has potentially lethal 'tools,' you must do all you can to ensure your first shot will be deadly.

Ethical shot distances are a fundamental consideration for bowhunters, as they directly affect both the success of the hunt and the welfare of the animal (and sometimes your own welfare). A bowhunter's primary responsibility is to ensure a clean, humane kill with minimal suffering for the animal.

Understanding and respecting your ethical shot distance is central to fulfilling that responsibility. This distance varies from hunter to hunter, based on a variety of factors such as skill level, equipment performance, and environmental conditions. The distance should always be within your ability to consistently place an arrow into the vitals of the animal under real-world conditions. It's not about what others consider "acceptable," but instead what you are confident in accomplishing with your gear, your shooting skill, and your arrow setup's terminal performance ability.